The Second Challenge in 150 years

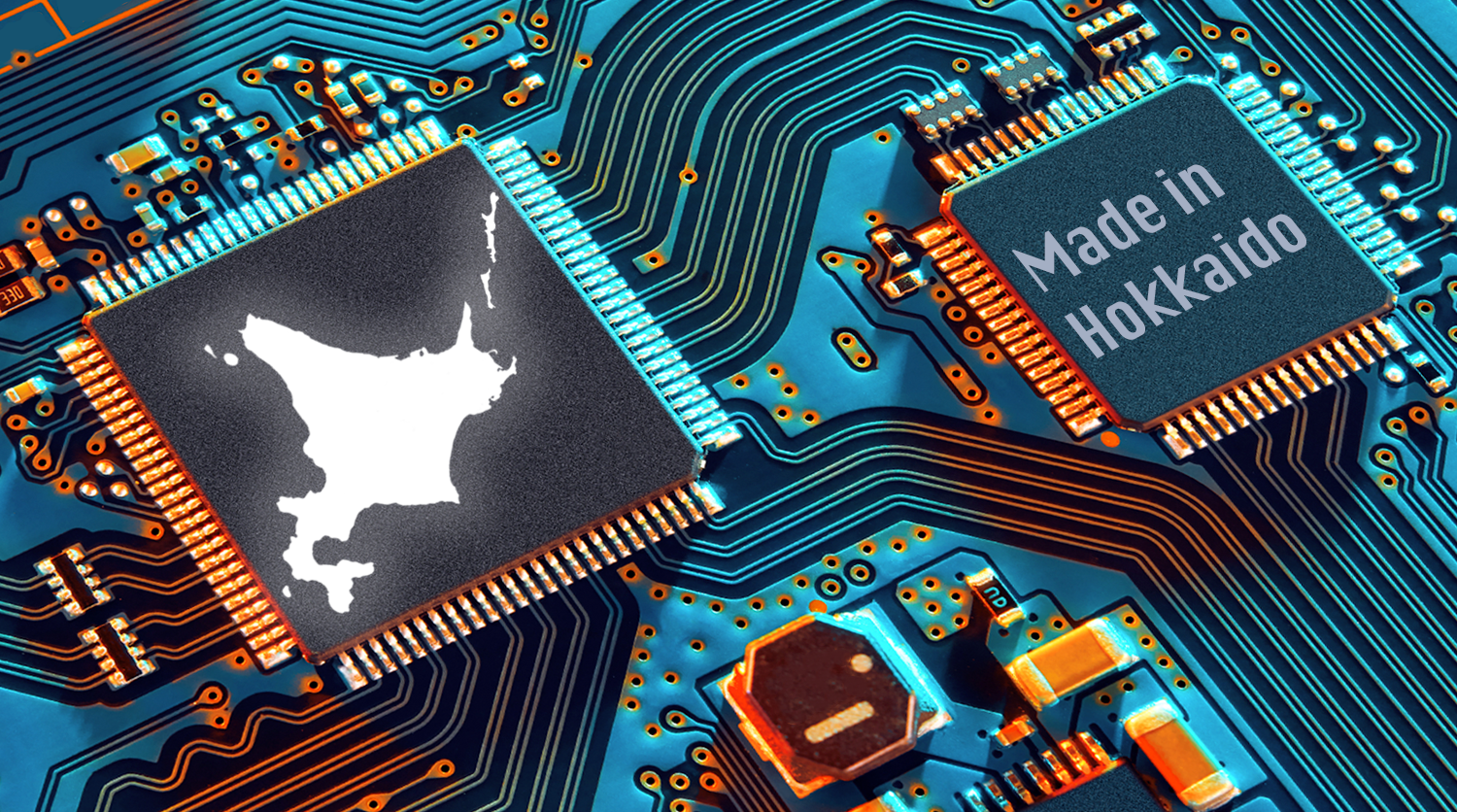

Hokkaido is rarely mentioned in the global news or media. However, since Rapidus, an advanced semiconductor company, decided to start its operations in Chitose, Hokkaido, the year before last, I have increasingly encountered the words “Hokkaido” and “Chitose” in the world's leading economic magazines and newspapers such as New York Times, Financial Times, and Forbes.

Many articles are, more or less, skeptical about the revival of Japan's semiconductor industry, which is attracting attention in the West. They objectively analyze the factors behind Japan's past failure in developing the semiconductor chip industry and suggest that it should avoid repeating the same mistakes. Many articles emphasize the geopolitical significance of advanced semiconductors, the need for cooperation between Japan, the US and Europe, and the expectation of chip production in Hokkaido. In particular, many of the articles discuss the production of 2nm advanced semiconductors — which is expected to be successful — but express concerns about the lack of business models and ecosystem in Japan. These articles offer extremely important advice for us.

In contrast, what I hear domestically are rather sobering critiques from the sidelines. It is not uncommon for me to exchange views with people from the political, business and academic worlds at informal occasions such as parties and functions. Among them are those who ask, “Will advanced semiconductors succeed?” and, “What if it fails?” — criticisms in the form of questions.

Non-specialists tend to hold such views, which could have collectively been the architects of Japan’s lost decades. Their concerns are often vague and unfounded, leading to the typical emotional fears and, therefore, the avoidance of challenges in those generations.

Objective analyses and stringent opinions on business models are essential and welcome. Success in advanced semiconductors can only be seen after overcoming many challenges, such as rigorous technological development, solid business strategy, uncertain international politics, and so on. It is clear that there is no such thing as a simple “failure” or “success”.

Looking back, something similar must have happened 150 years ago. In 1876, Dr. William S. Clark was invited from Massachusetts, USA, to serve as vice president of Sapporo Agricultural College, our predecessor. The mission of the college was “to establish education and research for cold-climate agriculture in Hokkaido.” It is easy to imagine that the mission was a complex task for Japan's northernmost university, which had just been founded to introduce advanced Western science.

Dr. Clark left the college after eight months, but the remaining American teachers and others continued the human resource development and research on cold-climate agriculture, some of which are still carried out today in the Faculty of Agriculture at Hokkaido University. In retrospect, the extremely tough project of establishing cold-climate agriculture was the accumulation of many failures and successes. Consequently, Hokkaido is now the food production center of Japan, producing 220% of its own population’s food requirements in terms of calories. Nevertheless, solving one challenge often creates another. The establishment of cold-climate agriculture is still ongoing.

Human resource development and research for advanced semiconductors is the second major challenge for Hokkaido University after Dr. Clark's challenge. In both cases, there is no small amount of concern about their success. This is not surprising, considering that both are unprecedented social implementations of advanced science.

In the New Year, I received some advice from US experts, to which I replied that we are already at the point of no return and the wheels have already started turning. After 150 years, a new challenge has just begun.